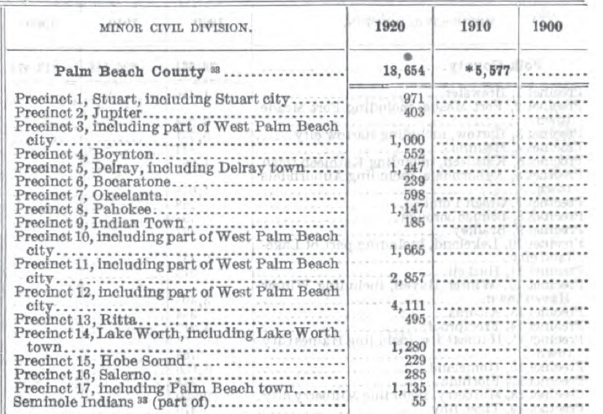

Over the years, as northern transplants settled the South Florida area, local residents have told stories about who founded the town of Boynton. Some stories were romantic tales of a gallant major, or of a not-so-gallant representative from Michigan.

So how was this present day city of 69,000 residents founded?

IT’S COMPLICATED

The best primary sources to unravel this tale are the land transaction records as recorded in the Dade and Palm Beach County courthouses, and newspaper accounts of the time. All persons who were here to witness the events have passed on.

The land grant applications as filed with the federal land office in Gainesville provide the first concrete information. Henry Dexter Hubel was born in 1853 in Ontario, Canada, and

H. Dexter Hubel

ventured to South Florida in 1877, filing a homestead application for 80 acres along the beach front just east of the present Boynton Beach downtown area. Though beach front land is extremely valuable today, it had little value in the 1800s as farm land, as thick Florida brush covered the land. The alluring part of that property was that there was a high ridge on the land over 20 feet high, hence today’s name of Ocean Ridge for the area.

Hubel’s stay on the property was short. He built a hut of palmetto leaves and driftwood, and sent for his family from Michigan, according to Charles Pierce, who wrote of the Hubels in his book “Pioneer Life in South Florida.” Soon after the family arrived, they managed to set the house on fire while cooking. The Pierce family put up the Hubel family, but the mean coastal landscape was too much for the Hubel family. They abandoned the claim. In 1880, another local resident took up the claim to the property along the ocean. Stephen Andrews, who was the House of Refuge keeper for shipwrecked sailors in what would become Delray Beach, filed a claim on the land and paid the federal government 90 cents an acre for the beachfront. Andrews probably did not do much with it, except perhaps raise some coconuts.

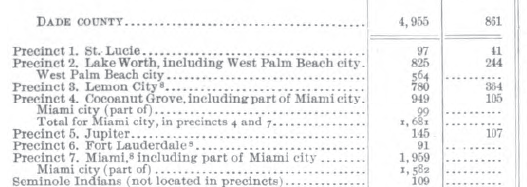

Meanwhile, the state of Florida encouraged development of the South Florida frontier by offering significant amounts of land for improvements such as canals and railroads. The Florida Coast Line Canal and Transportation Company made plans to dig a canal from Biscayne Bay to Lake Worth in 1881. In 1889, the Florida Legislature granted the company one million acres of land to dig the waterway from the St. John’s River to Biscayne Bay by connecting existing bodies of water such as Lake Worth and the Indian River.

The land the state of Florida granted in the Boynton area was west of Andrew’s beach front land, on the west side of the marsh that separated the high ocean ridge and the coastal ridge further inland. This low marshy area is what would be widened and deepened to become the Florida Coast Line Canal, today’s Intracoastal Waterway. The canal company charged a toll on the canal to help pay for its construction.

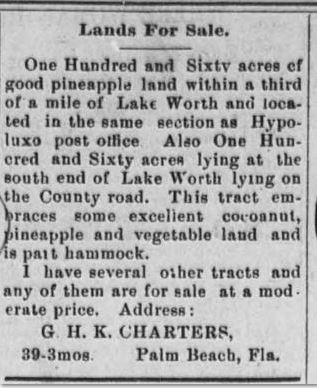

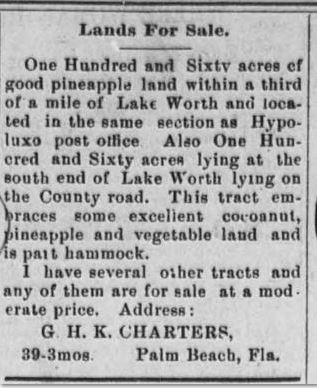

As an additional means to raise funds for canal construction, the Canal Company began to sell its land holdings to settlers. One such parcel was a 160 acre plot just west of the ocean ridge. George H.K. Charter bought this land in 1891 for $240. George had land on the barrier  island about where Manalapan is today, and intended to grow coconuts and pineapples on his new property. Land along the west side of Lake Worth further north was known as the most fertile land in the area, with farmers producing tomatoes, sweet potatoes, pineapples, bananas and other crops. These “Hypoluxo Garden Lands” supported many early farmers as they shipped their produce up Lake Worth for loading on larger ships headed for the northeast.

island about where Manalapan is today, and intended to grow coconuts and pineapples on his new property. Land along the west side of Lake Worth further north was known as the most fertile land in the area, with farmers producing tomatoes, sweet potatoes, pineapples, bananas and other crops. These “Hypoluxo Garden Lands” supported many early farmers as they shipped their produce up Lake Worth for loading on larger ships headed for the northeast.

But Charter got the idea to head to Jamaica, so he sold his holdings in the area. The November 1891 Tropical Sun newspaper carried an advertisement for the 160 acres of land “lying on the County road.” This was the “sand road” that Guy Metcalf built to allow road passage via covered wagon between Lantana and Lemon City, and ran about where NE 4th Avenue runs through downtown Boynton Beach today.

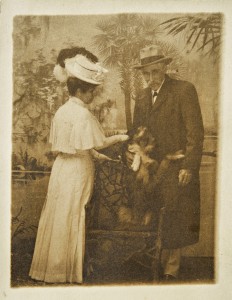

Byrd Spilman Dewey, who lived about one mile south of present day West Palm Beach, saw that ad and purchased the land on January 25, 1892 for $700. Mrs. Dewey and her husband Fred S. Dewey had homesteaded land on Lake Mangonia in the late 1880s.

The Deweys

Mrs. Dewey wrote a weekly column for the local newspaper The Tropical Sun, in addition to writing for many of the major woman’s periodicals of the time such as the Christian Union and Good Housekeeping. It is not known if the Deweys did any improvements to the land in the early 1890s.

In 1893, South Florida’s king had arrived – Henry Morrison Flagler. Land values soared as Flagler commenced to build one of the largest hotels in the world, the Hotel Royal Poinciana. Northerners flocked to the area in search of the winter paradise and the prospect of making money on the lands in the areas around Palm Beach.

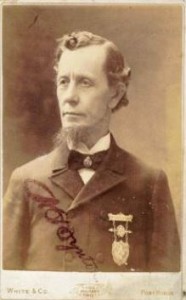

Enter the picture two men from Michigan – William Seelye Linton and Major Nathan Smith Boynton. The younger of the two, Linton, was the “talker” and dealer. They commissioned a boat, the Victor, with Frederick Voss at the helm, to take them south in 1895 on the newly opened canal. They sailed through the vast undeveloped country and surveyed what lands they wished to buy. Linton offered Mrs. Dewey $6,000 for her land, and offered Stephen Andrews thousands more for the oceanfront, with Major

Nathan S. Boynton

Boynton as the silent partner on the oceanfront property. Boynton then set about to build his 50 room hotel on the oceanfront, which became a well-known spot for its fine dining and location close to the Gulfstream and its warm waters.

Linton bought the Dewey land on the west side of the canal under a “contract” which meant the Deweys still held the deed, and Linton would pay them $1,500 a year over four years. The Deweys retained 40 acres of the land along the canal. Linton platted the land into lots and began selling them (although Linton filed no official plat with the county) and issued deeds to the buyers, who typically paid $50 per lot. If all the lots had sold, the lots would have grossed Linton well over $12,000.

But money problems soon plagued Linton on all his mortgaged land in the Boynton area and south in the town of Linton, which he had platted. He was insolvent. Settlers in Linton and Boynton now held worthless deeds to lands they had “bought” from Linton. Boynton tried to salvage the situation in the Boynton area by “buying” the 40 acre town site from Linton in March,

William S. Linton

1897. Seeing how things had unraveled in Linton, the Deweys were not in the dealing mood. In October 1897, the Deweys filed a foreclosure lawsuit against both Linton and Boynton. They settled in November with Boynton turning over money he had collected for lots, and the Deweys regaining all their lands. The Deweys could then issue deeds for the lots that were legal to the settlers. Folks in Linton were not so lucky. They had to pay twice for their lots, once originally to Linton, and then to the new creditors. The town folk were so upset that they took Linton’s name off the town and changed it to the Town of Delray.

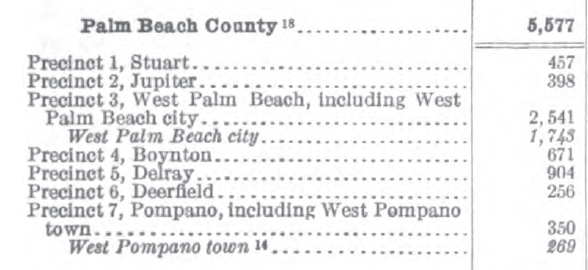

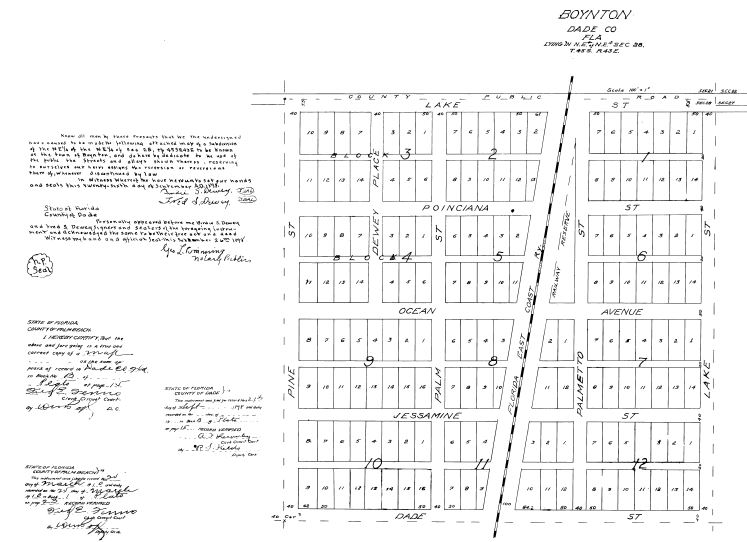

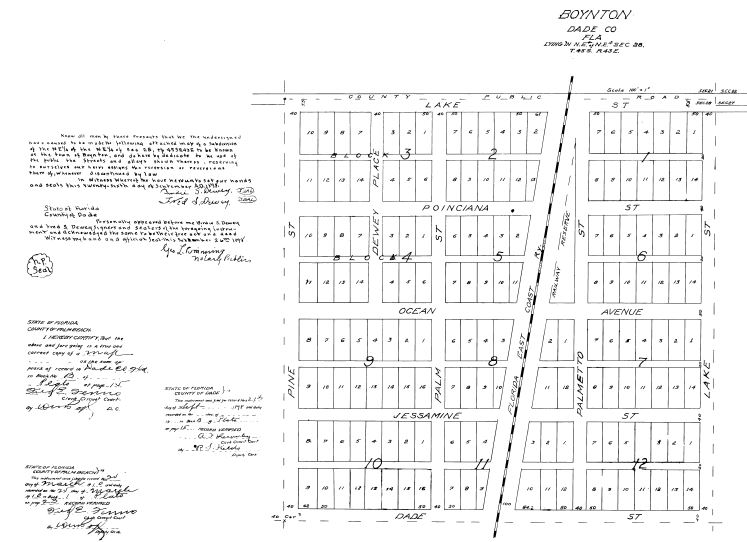

On September 26, 1898, Fred Dewey and Byrd Spilman Dewey (Birdie S. Dewey) filed the plat for the Town of Boynton in the Dade County Courthouse. A few days later they also filed the plat for Dewey’s Subdivision, where the Deweys divided the remaining lands along the canal into five acre farming tracts.

Fred Dewey took a job with the Florida East Coast Railway land company, and sold lands on behalf of the railway owned by Flagler. His territory was Boynton south to Pompano Beach. The Deweys built a home in Boynton, and Fred Dewey planted the first substantial citrus grove in Boynton, along the canal just south of present day Ocean Avenue. The Deweys supported the fledging town in many ways, including donating lots for the Methodist church, donating the proceeds from lots to pay for road improvements,

Plat Signatures

advocating for Boynton to have its own school, and donating books in 1910 to start the first “free reading room” in Boynton, where the books were held in the post office.

So one question remains: why did the Deweys keep the town named Boynton? Speculation must be used here as no definitive answer was found. One simple explanation is in the post office name. With no zip codes at that time, town names had to be distinctive. If one town already had taken a name, another town in the state could not have the same name. With Delray the next stop on the train line, confusion would have resulted if the Town of Dewey were right next to the Town of Delray.

The Deweys left Boynton in 1911 as Mr. Dewey’s health deteriorated. The military hospital in Johnson City, Tennessee admitted Fred with many ailments. He would linger in military hospitals until 1919, when he passed away. Mrs. Dewey would eventually retire to Jacksonville, where she passed away in 1942.

The Dewey’s role in founding and saving the Town of Boynton was largely forgotten, and the legend of Boynton largely supplanted their story. Major Boynton passed away in 1911, and his

Byrd Spilman Dewey

family continued to run the hotel until 1925. At the height of the land boom, Boynton’s family sold the hotel and land to the Harvey Corporation which had plans to build a luxurious hotel on the site. The new owners demolished Boynton’s hotel, but the grand hotel was never built. The 1926 and 1928 hurricanes and the crash of 1929 saw to that.

The residents incorporated the the Town of Boynton in 1921, thus finally cementing Boynton’s name as the moniker for the town. To help construct the woman’s club building, designed by Addison Mizner, Boynton’s family donated $25,000 to the Boynton Woman’s Club as a memorial to their father.

As was said in the beginning, the story is complicated.

Each player in the story contributed something different in the genesis of what is today’s Boynton Beach.

Plat for the Town of Boynton