West Palm Beach’s Mandel Library on Clematis Street has a wonderful collection of Florida books, maps and rare documents. Among the most fun are old city directories, which people used to find persons and businesses. The earliest edition in the library’s collection is from 1916. The advertisements list businesses, hotels and restaurants of almost a century ago.

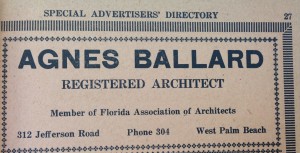

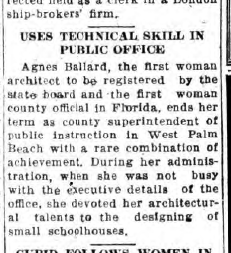

One such ad intrigued me. It stated “Agnes Ballard – Registered Architect, member of the Florida Association of Architects.” I thought that was unusual, to have a woman in business for herself in such a male dominated field.

Agnes Ballard’s ad from the city directory

When back at a computer, I began an Internet search on her life. And the story that unfolded had to be documented so that someone who lived in Palm Beach County for over 60 years and contributed so much to its betterment would not be forgotten.

Agnes was born September 14, 1877 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the daughter of Dana and Jennie Ballard. Her father’s occupation on the 1880 Census was listed as “driving a job wagon.” But a different path other than menial labor was meant for Agnes. In 1905, she graduated from the State Normal School in Worcester (the teacher’s college) with a teaching certificate. She also attended Wellesley College and Oxford in England. Her first teaching stint was in Palmer, Michigan, but the cold weather and snow were too much for her. “I wanted to go somewhere where I never would see snow again.”, she told the Palm Beach Post in 1958.

In 1906, at the age of 29, she set out on a grand adventure that landed her in West Palm Beach, Florida, a single woman seeking her fortune. In 1906, the school board approved her appointment to teach 6th grade. Later, she was one of the first teachers at the Palm Beach High School, teaching geography, biology and chemistry. In 1908, she worked at Grace Lainhart’s private school north of downtown where she taught Latin and mathematics. Her income was tight, so she took a better paying teaching job in New York. The cold proved too much and she was back in the spring, finishing out the term teaching in St. Augustine.

But her interest in learning architecture could not be accomplished in Florida. Instead she took a job as a secretary in LaCrosse, Wisconsin to study architecture in the firm of Percy Dwight Butler, according to author Sarah Allaback in her book The First American Woman Architects. It was not uncommon for students to learn architecture by apprenticing in a firm, rather than through formal study in a university, and she did so from 1911-1914. Once she learned her craft, Ballard returned to West Palm Beach in 1914 and began practicing architecture. Her ad from a 1916 Palm Beach Post listed her office as 224 Clematis Street, and her drafting room as 312 Jefferson Road, which also served as her home. She ran several newspaper ads in both the Palm Beach Post and the Palm Beach Daily News for her architectural services. In 1915, she became the first registered woman architect in the State of Florida, according to the Report of the Secretary of the State of Florida. She was one of 82 registered architects in the state. Addison Mizner befriended Ballard and together they founded an architect’s club, with Mizner as president and Ballard as secretary. She was not too impressed with him: “He was very clever with original designs, but I still think he was lazy.”

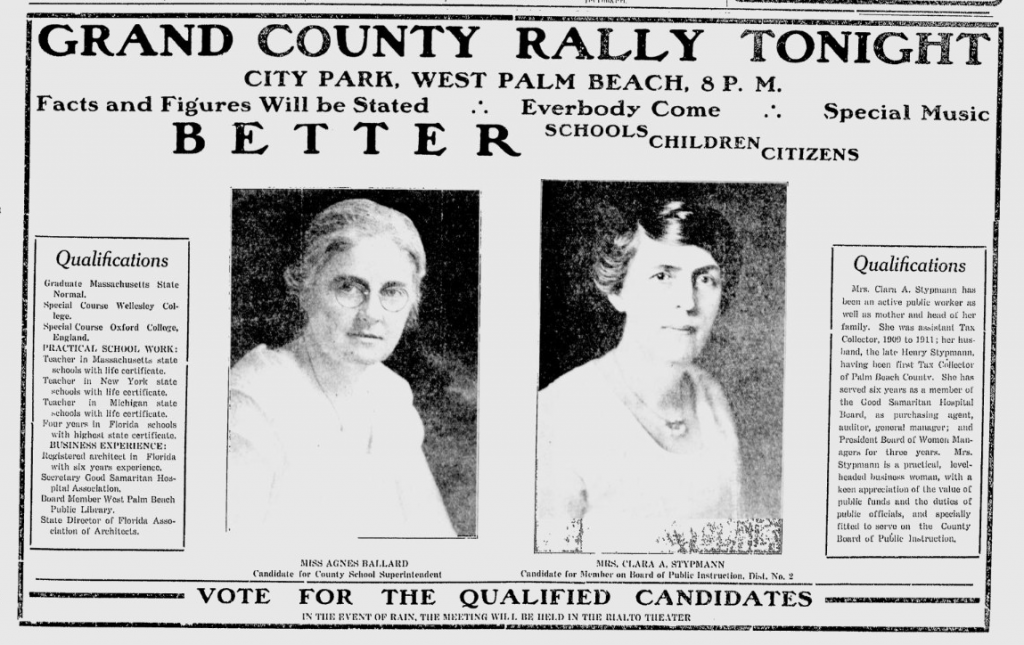

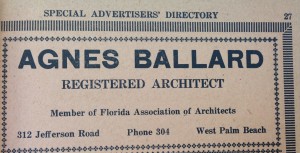

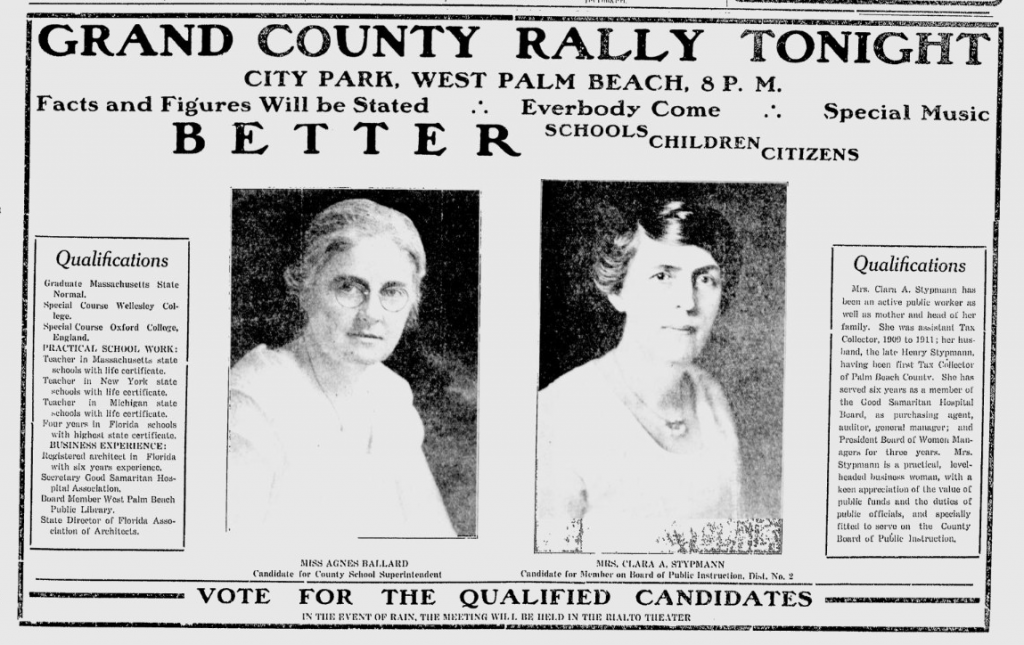

But a monumental event in 1920 was to drive her career in a completely different direction. On August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, granting woman’s suffrage. Not only could women vote, but they also could run for public office. And Agnes Ballard did just that. She ran for the position of Palm Beach County Superintendent of Public Instruction. The League of Women Voters supported Ballard and Clara Stypmann, who ran for school board, and held rallies around the county to get women to register to vote. The campaign was heating up in September. The Palm Beach Post wrote September 17, 1920: “And with a political cartoon too! Little Johnny and Mary, school books under arms and hand-in-hand, stand on the shores (of time) calling for help, which help seemingly is to be rendered in the golden dawn, for Miss Agnes Ballard is the rising sun.” She wrote new lyrics for a popular tune of the time as her campaign song (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8kNpGTPbvk).

Campaign ad for Ballard and Stypmann

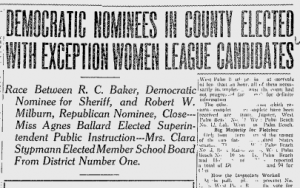

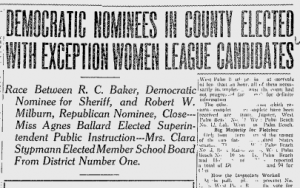

Election day – November 2, 1920. Turnout among the voters was good, and the first vote by Palm Beach County’s women was a success – both Agnes Ballard and Clara Stypmann won their elections. Neither had run on the Democratic nor Republican ticket, and Ballard beat both the Republican Kishpaugh and Democrat Bell by more than 500 votes, thus becoming the first woman elected county official in Florida. “On election night I recall standing on Clematis Street near Olive Street watching election returns being flashed on the side of a building. Shortly before 11 o’clock my name was flashed as a winner in the school election. I was so excited I didn’t go home until 2 o’clock the next morning.”

Ballard took office January 4, 1921, and faced an underfunded and exploding school district.

Ballard wins election

The 1920s boom was on, and each day new residents arrived with children in tow, wanting to enroll in school. She floated bonds to pay for school expansion at several of the area’s high schools, and even designed some of the smaller schools herself. She also urged teachers to have students attend the fledgling Palm Beach County Fair “The children can learn more Palm Beach County geography and conditions agricultural and otherwise in one day at the fair than perhaps days of study from ten books.”

Building of new schools couldn’t happen fast enough. In 1923, schools at Boynton and Jupiter were holding double sessions . To expand, $35,000 in bonds were issued for school expansion. But taking care of schools wasn’t Ballard’s only vocation. She continued her architecture practice, but also advocated for “Near East relief” – “If everyone in this city would contribute 10 cents for Near East relief then no one would have to give until it hurts and Palm Beach County would go far above its quota of $3,000. ”

To beautify local streets, she urged county commissioners to grant her permission to plant Australian pines and Royal Palms along the Dixie Highway, and they granted that in 1922. In education circles, she assumed leadership roles, being elected president of the Royal Palm Educational Association, an alliance of Dade, Broward and Palm Beach County schools. In 1924, she decided not to run for reelection to the office of superintendent, wanting to spend more time in architecture. Joseph A. Youngblood took over in 1925. She returned to architecture and with the land boom on, she saw the opportunity to make money in real estate.

With her earnings, she took extensive trips to Europe in 1926 and in 1928. But in the depths of the Depression, architects could find little work. In 1933, she contacted Superintendent Youngblood about a teaching job and was granted one at Conniston Road School. In 1934, she began teaching at Palm Beach Elementary School, where she remained until 1947. At that time she resumed her architecture career full-time, employing two draftsmen to keep up with the work. She designed houses, apartment buildings, and often taught technical drawing classes at the high school at night for adult students. One of the homes she designed in Palm Beach was demolished in 2009. No detailed record of her designs in Palm Beach County exist.

With this busy schedule, she still managed to continue her education. By attending in the summer, Ballard earned her B.A. degree from the University of Florida in 1936. She met Dr. John I. Leonard there, who was busy getting Palm Beach Junior College started. She wanted to help the effort, so she donated a large portion of her book collection to the fledging college and its library.

In civic circles, she was very active in the Girl Scouts, often guiding them on beach walks to learn the constellations, as astronomy was another hobby of hers. She was an active  member of the Bethesda-by-the Sea episcopal church, the West Palm Beach City Library, the Society of the Four Arts, and the Women’s Garden Club. The library work had to have been a bit of a sore-spot. She was initially chosen to design the Memorial Library in Flagler Park, but was later dropped in favor of the Harvey and Clarke firm.

member of the Bethesda-by-the Sea episcopal church, the West Palm Beach City Library, the Society of the Four Arts, and the Women’s Garden Club. The library work had to have been a bit of a sore-spot. She was initially chosen to design the Memorial Library in Flagler Park, but was later dropped in favor of the Harvey and Clarke firm.

She attempted to reenter politics in 1957 when she ran for school board at age 80, though she was unsuccessful. As she retired, she became more active in local organizations, especially in gardening and church work.

When the Daniel Hulett Children of the American Revolution Society installed its officers in 1961, Ballard was on hand to swear them in at age 84, in the old red school house in Palm Beach. Agnes Ballard died November 24, 1969 at the age of 92 after living at 415 Hampton Road for many decades. Her house was demolished when the parking lot for the then “Sears Town” was expanded. Her obituary in the Palm Beach Post said the following about Agnes: “If knowledge is power, and modesty a real attribute, thoroughly mix with a keen sense of humor and you will have Miss Agnes Ballard.”

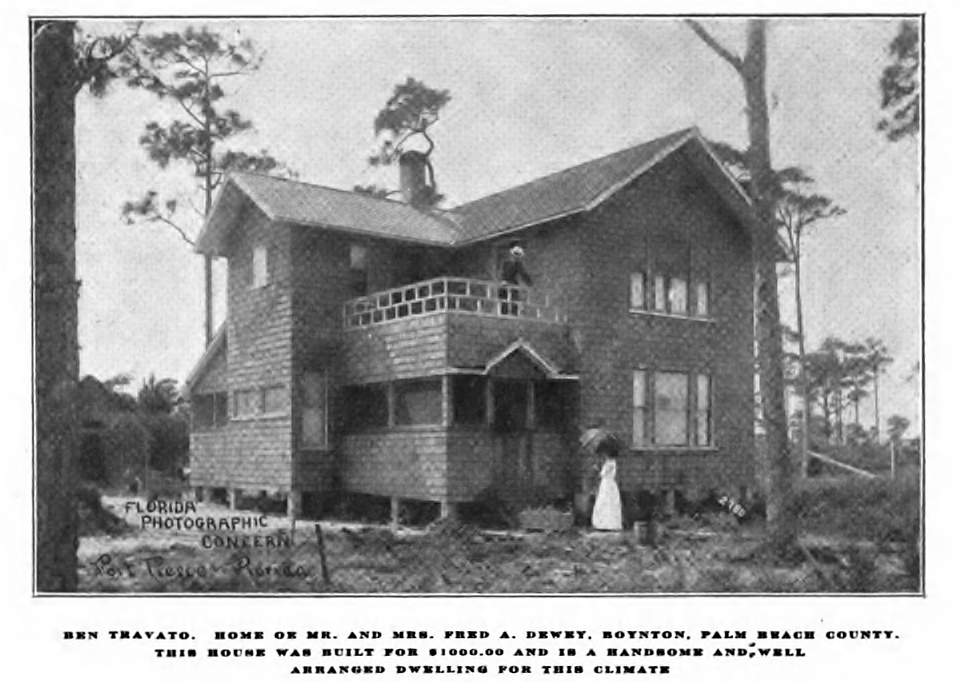

A house designed by Agnes Ballard at 411 26th Street in Old Northwood, 1951.

Agnes Ballard was a renaissance woman who lived a life as she saw fit – unconventional, challenging, and fulfilling. The pathway she blazed through the jungle for women today is one we think was always there as millions traverse it each day. But someone had to take that first swipe at it here in Palm Beach County. And it was Agnes.

This story was researched through the Mandel Public Library, the Palm Beach Post archives, the Miami Metropolis archives, and several books at Archive.org and Google Books.

UPDATE: Agnes Ballard was featured in the Palm Beach Post July 10, 2016 – http://www.mypalmbeachpost.com/news/news/local-govt-politics/this-trailblazing-woman-was-first-hillary-clinton-/nrsy5/

Agnes Ballard is also featured in the book “Legendary Locals of West Palm Beach.” – https://books.google.com/books?id=ml1UCwAAQBAJ&lpg=PT35&ots=MsIMR9ap-E&dq=agnes%20ballard%20palm%20beach%20post&pg=PT35#v=onepage&q=agnes%20ballard%20palm%20beach%20post&f=false