POINCIANA STEM ELEMENTARY SCHOOL HISTORY

THE MAJESTIC ROYAL POINCIANA TREE

May and June are the months when royal poinciana trees bloom the brightest. Their red, flame-colored flowers add brilliant color to the South Florida landscape. A commenter on the Historic Boynton Beach Facebook page declared that the late spring signature flowers are Florida’s version of leaves changing color in the fall.

Royal Poinciana Tree in bloom

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Boynton’s Poinciana STEM Elementary School is named after the massive umbrella-shaped royal poinciana tree. The name alone evokes Florida’s lush, tropical beauty. David Fairchild brought the first of these Madagascar natives to South Florida when his wife planted one in their Miami front yard in 1917. The trees thrive from Key West north to West Palm Beach and it’s likely that Boynton Garden Club members beautified Boynton by planting royal poinciana seeds here in the 1930s or 1940s. According to the University of Florida, the trees bear flowers between four and 12 years after planting.

LET’S BUILD A SCHOOLHOUSE

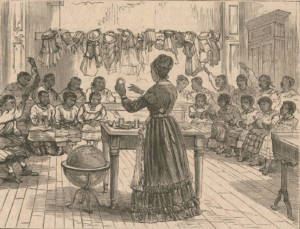

Typical 1900s Black School (courtesy NYPL)

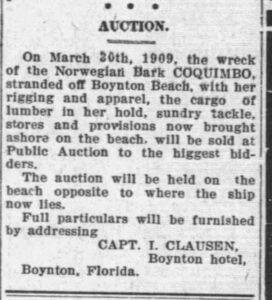

Many people don’t realize that Boynton Beach’s Poinciana Elementary School had its humble beginnings as an informal school operated by African Methodist Episcopal church members. St. Paul’s AME Church, constituted in 1900, is Boynton’s oldest church.

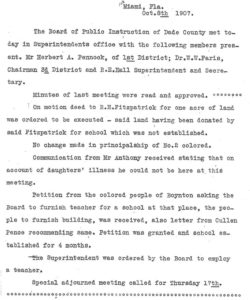

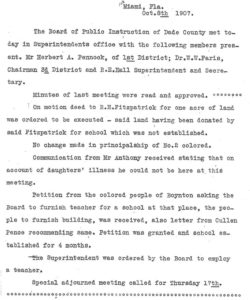

The school received government funding after 1907 when the black community petitioned the school board to furnish a teacher, but the residents were to provide a building. The petition was accompanied by a letter of support from farmer and fruit shipper Cullen Pence, a community builder who donated land to the city for a ball field and helped with many town improvements.

1907 Board of Public Instruction of Dade County minutes

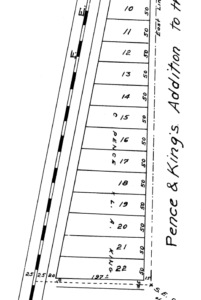

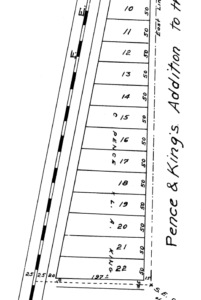

Pence & King’s Addition 1908

The one-room wooden schoolhouse was situated on Pence & King’s Addition (Federal Hwy. north of Boynton Beach Blvd.), a tract laid out by Pence and black pioneer resident L. A. King in 1908. This suggests that Mr. Pence furnished the land and wooden school building and the school board paid for a teacher. Newspaper accounts and school board records show that by 1909, when Palm Beach County separated from Dade County, the school’s official name became Boynton Negro School.

Let’s look back at how the fledgling school, like the brilliant tree it’s named for, took root, and blossomed.

SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL

Under the “separate but equal” doctrine of the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, segregated schools were expected to provide a comparable education and experience for black and white students. On the contrary, black students received second-rate treatment; the buildings were substandard; teachers were paid substantially less than white teachers; supplies were meager, and schools often received desks, books and slates discarded from white schools. The school year too, was shortened for Florida’s black students so the children could work in the fields during winter harvest.

THE TOWN GROWS

Picking Beans (Broward County Library Digital Archives)

By 1910, the unincorporated town of Boynton had grown to over 600 residents. The Board of Public Instruction paid to erect an opulent new two-story concrete block school in the 100 block of Ocean Avenue for Boynton’s white students. The modern school had indoor plumbing, gleaming blackboards, and spacious classrooms with large windows and door transoms for ventilation and natural light. In juxtaposition to the overcrowded one-room Negro School, the new Boynton School for white students had a fancy bell-tower and six classrooms. When the school opened on September 8, 1913 it enrolled 81 pupils between grades one and twelve.

Boynton School (for white students) 1913

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON AND JULIUS ROSENWALD

In the 1910s, an unlikely pair helped improve education for black children in the rural south. Boynton, a farming community, was indeed rural. In 1912, Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington invited Jewish-American philanthropist Julius Rosenwald (then president of Sears, Roebuck & Co.) to serve on the Tuskegee board of directors to help black education, where segregated southern schools suffered from inadequate facilities, books and other resources. Rosenwald’s 1917 school building fund encouraged local collaboration between blacks and whites by providing seed money and requiring communities to raise matching funds. Between 1917 and 1932, Rosenwald funded 5,357 community schools and industrial shops in 15 southern states.

Julius Rosenwald & Booker T. Washington in 1915 (Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library)

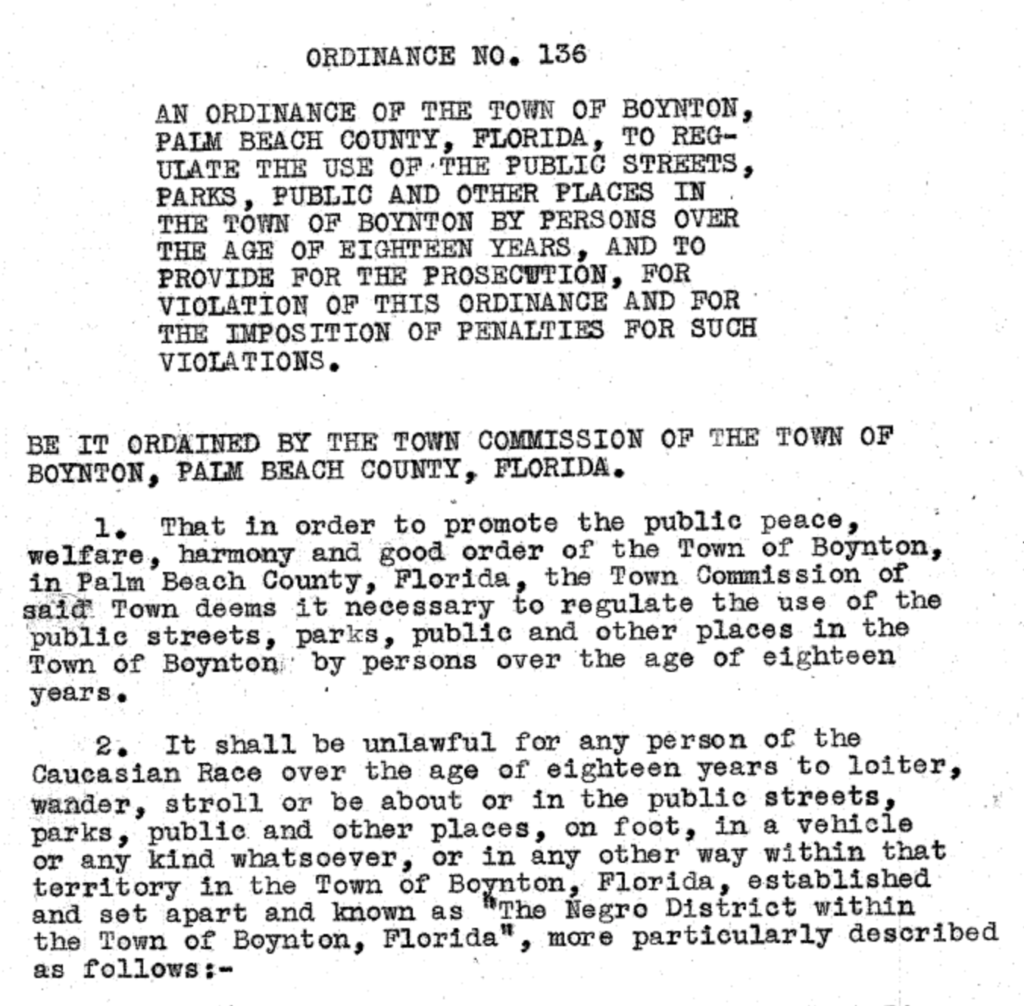

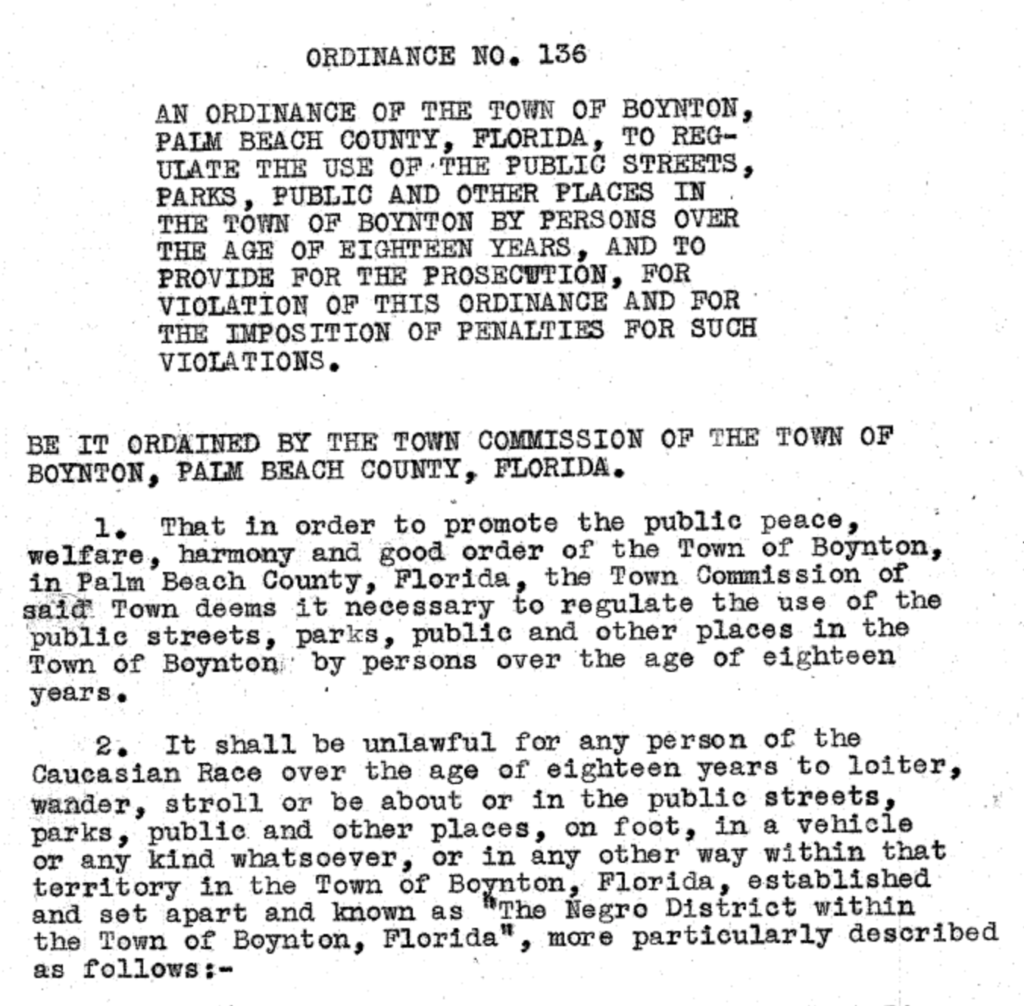

ORDINANCES 37 and 136

The Town of Boynton imposed segregation in 1924 with Ordinance 37. This forced black residents, businesses, churches, and the school to move west. Ordinance 136 passed in 1933 stipulated that black residents stay in the designated “colored town” from sundown to sunup.

JULIUS ROSENWALD SCHOOL BUILDING FUND

The Rosenwald funded Boynton School after the 1928 Hurricane (State Archives of Florida)

The Boynton Negro School located on the west side of Green Street (now Seacrest Blvd.) and today’s NE 12th Ave. was the first Rosenwald funded school in Palm Beach County. In 1925, at the height of Florida’s great 1920s land boom, the Rosenwald Fund contributed $900 in seed money toward a new four-room, three teacher Boynton Colored School. The fund also provided architectural plans and specifications for the schoolhouse.

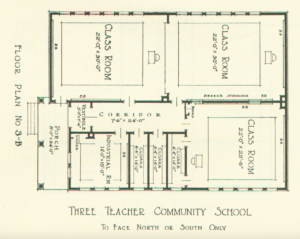

THREE TEACHER COMMUNITY SCHOOL

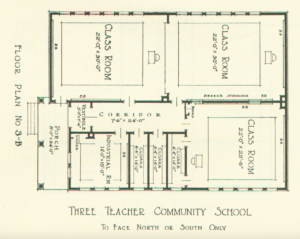

Building Plans, Three Teacher Community School, 1924

Building Plans, Three Teacher Community School, 1924

The Tuskegee architect approved community school design included a porch, three classrooms and an industrial room, running water, and indoor toilets. Black community members raised $100 and the white community donated $4,000 with the Palm Beach County Board of Public Instruction paying the last $12,000. Its four rooms served grades one through eight until 1952 when the building was no longer big enough to handle the number of students. Six further classrooms were built to the west.

Ten other Rosenwald-funded schools followed in Palm Beach County. After the devastating September 1928 hurricane left the Boynton school intact, the damaged or leveled most other Palm Beach County schools. School Superintendent Joe Youngblood petitioned the Rosenwald Fund for emergency monies. By 1931 Rosenwald schools and industrial trade shops were operating in Jupiter, Boca Raton, Delray Beach (shop), West Palm Beach (school, shop), Pahokee, Belle Glade, South Bay, Kelsey City, and Canal Point (school, library).

Boynton Negro Elementary School, 1950. Teacher Blanche Hearst Girtman (Boynton Beach City Library Local History Archives)

OVERCROWDING

Boynton Negro School Basketball Team members, 1942 (Boynton Beach City Library Local History Archives)

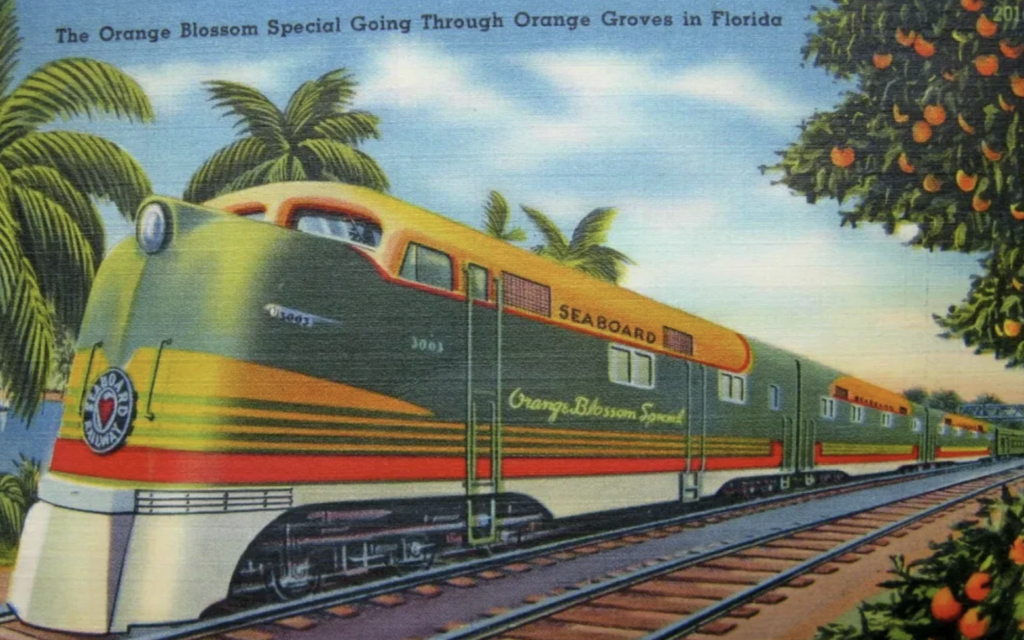

In the mid-1940s, rural black schools consolidated. The Lake Worth Osborne Colored School that had operated out of a church combined with the Boynton School.

In the area west of Boynton/Hypoluxo/Lantana, the Rangeline School on Rte. 441 taught children of farmers and migrant workers in a World War II Quonset Hut.

Students entering Poinciana School, teacher Blanche Hearst Girtman

In reaction to the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, school leaders decided to rename “colored” schools after local points of interest. In June 1954, the Boynton Colored School became Poinciana School. The 1950s were a time of rapid growth in Palm Beach County. The district added a Poinciana Annex building with six additional classrooms located at 121 NE 12th Ave. next door to the original school in 1952.

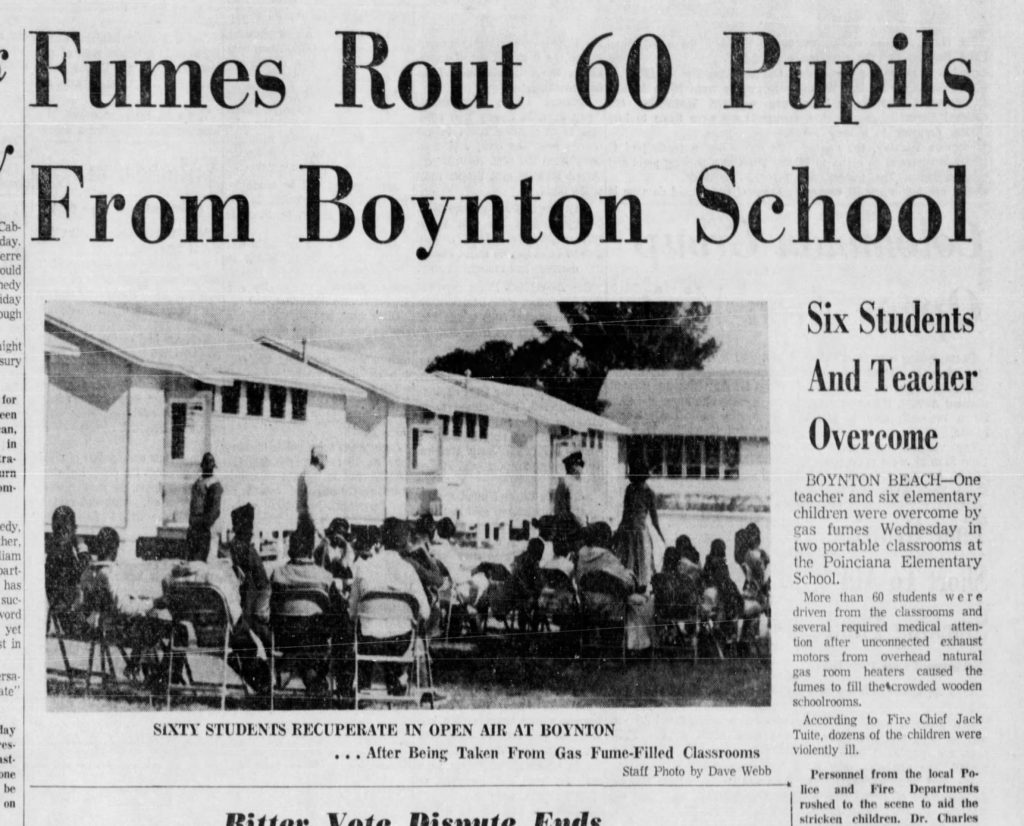

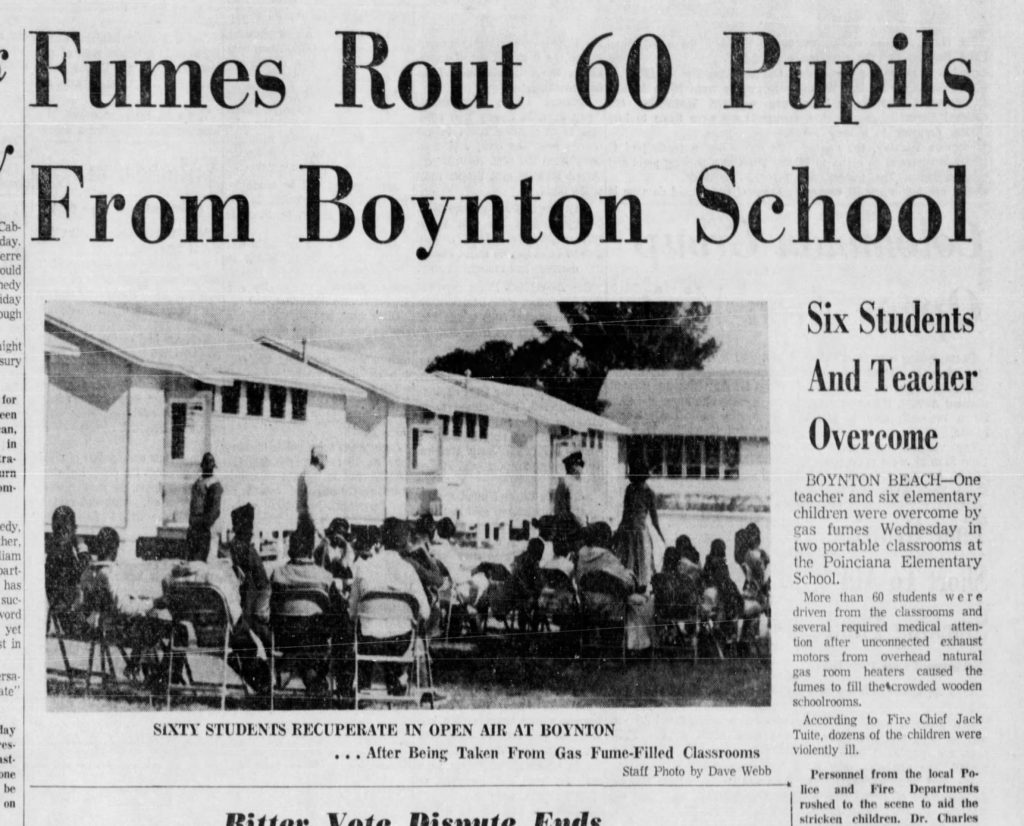

By the 1960s overcrowding (over 700 students in 18 classrooms) forced double sessions with some classes held outdoors and in hot, cramped portable classrooms that Fire Chief Jack Tuite called “death traps.”

Fumes Evacuate Poinciana Portables (The Palm Beach Post, 16 Dec. 1960)

DESEGREGATION

In March 1962, the school board approved a land purchase of more than a half-acre for a Poinciana School addition to accommodate a junior high school. That same year Rev. Randolph Lee of St. John Missionary Baptist Church led efforts to establish a high school for black students. The closest high school for black students was Carver Industrial High School in Delray Beach. Students who wanted an education had to bus there from all over the region.

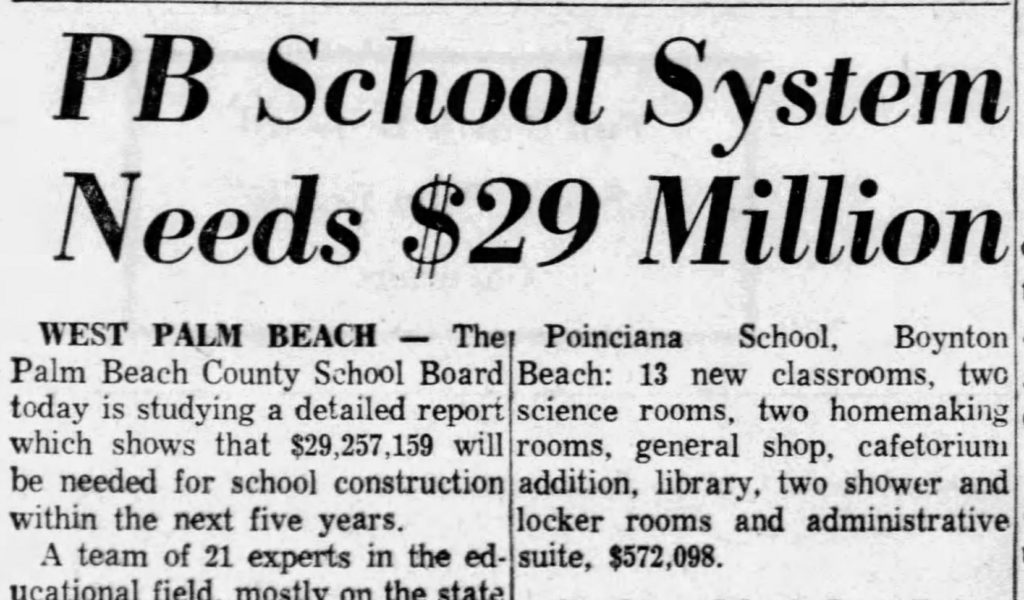

A $362,000 new school was planned for 1963, about the same time that Palm Beach County Schools began integration. The district had difficulty getting the site owner to sell as originally agreed. Furthermore, the school district had a large list of new school projects and improvements. In October 1963 the district was trying to prioritize the multiple projects, including a proposed $572,000 new Poinciana elementary and middle school that would include 13 classrooms, science rooms, industrial and home economics shops, a library, cafetorium [cafeteria/auditorium], locker rooms, and an administrative suite.

School System Needs $29 Million (10 Oct 1963, Fort Lauderdale News)

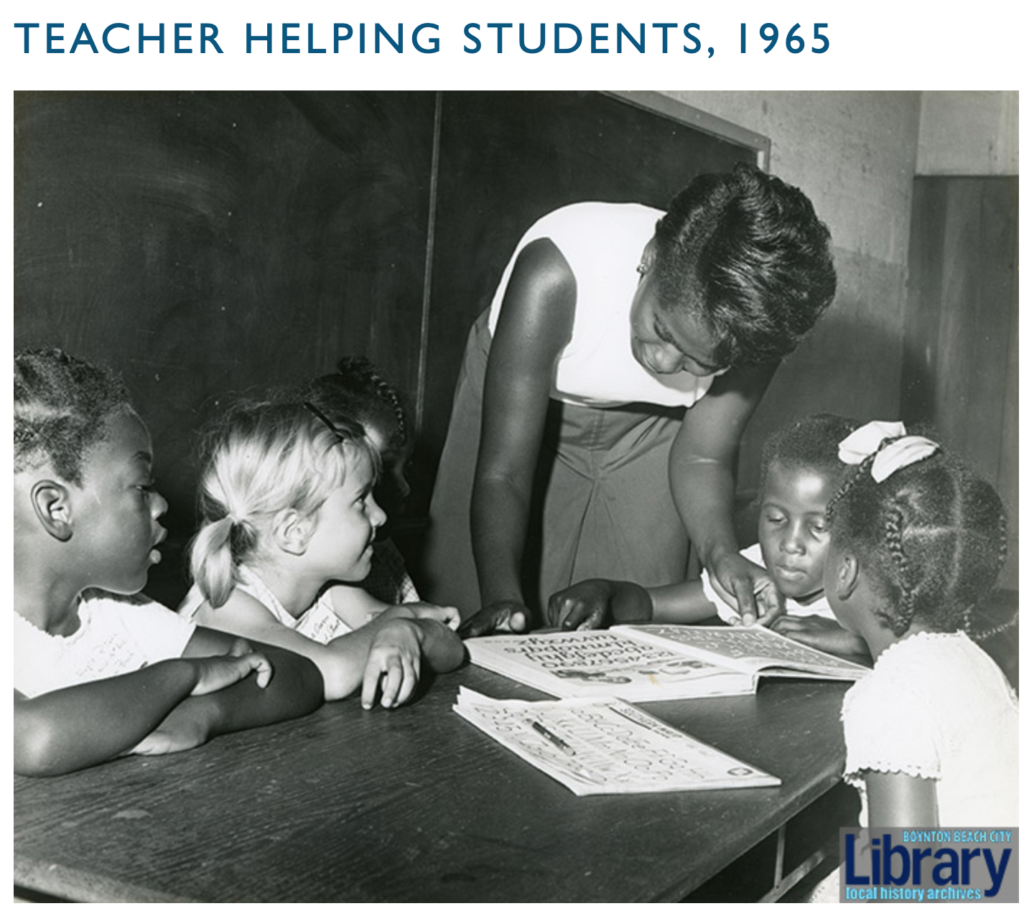

Meanwhile, school integration did not go smoothly. It turned out that most black families and white families wanted their children to stay in the neighborhood and not be bussed across town. A May 1965 Miami Herald article about school desegregation reported that the boundary lines for Poinciana School in Boynton Beach had been precisely drawn to encompass the negro residential section.

Poinciana Elementary School 1962 (Boynton Beach City Library Local History Archives)

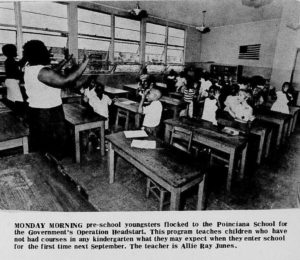

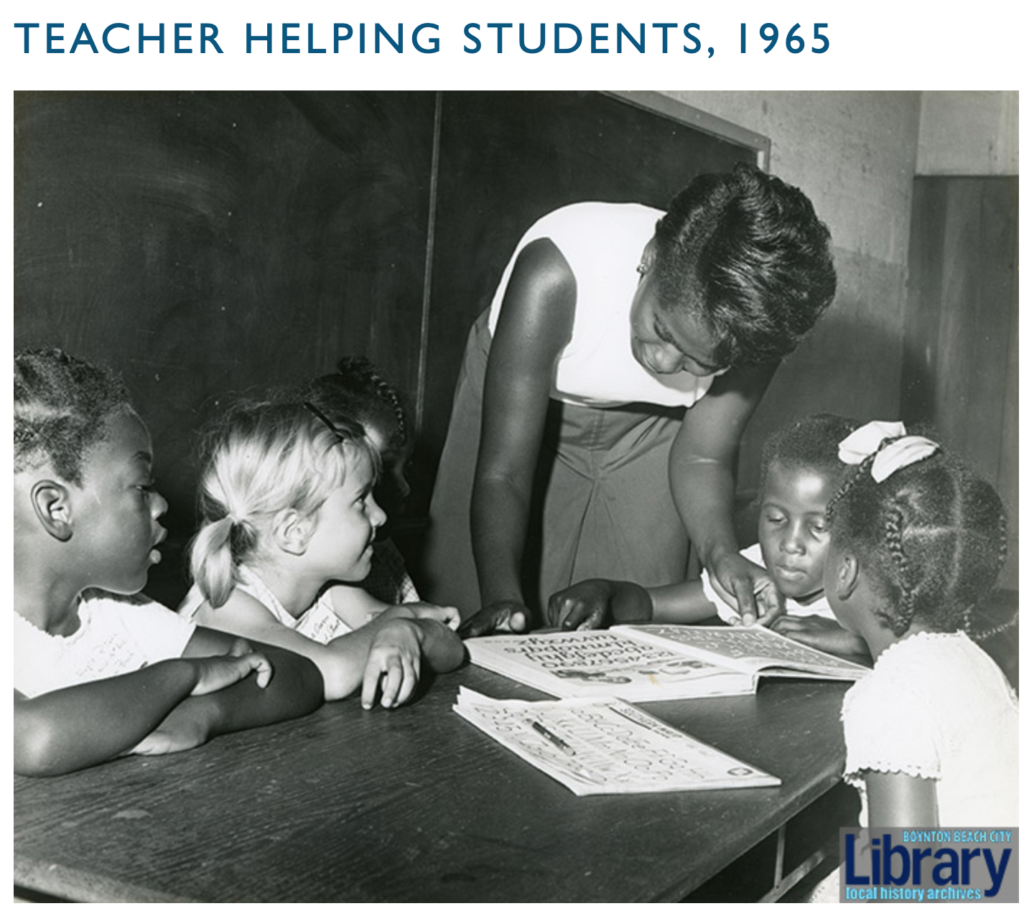

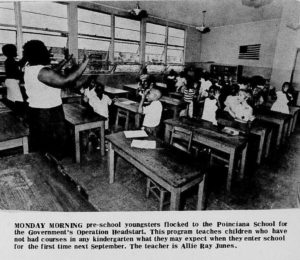

Head Start (Boynton Beach Star 17 Jun 1965)

Poinciana became a site for the federally funded Head Start program for children not enrolled in private kindergarten in 1967.Sarah Costin and Lena Rahming incorporated the Boynton Beach Childcare Center about that time and worked with community leaders to build a separate building for preschool and kindergarten aged children.

By 1969, school officials agreed to remove grades 7-8 from Poinciana School, a decision that forced 42 students to integrate into Boynton Junior High (now Galaxy Elementary School). Integration was so much stress for students and families of both black and white students that some students enrolled in private school and other students simply dropped out of school.

NEW MAGNET SCHOOL

The dilapidated school building saw its last days in late 1995, when it was razed for a larger, modern school. The Palm Beach County School Board built a brand new, closed campus Poinciana Elementary School that opened as a Math/Science/Technology magnet school in August 1996. With over 97,000 square feet and a Planetarium, the school occupies 8.7 acres, backing up to the Carolyn Sims Recreational Center.

Poinciana STEM Elementary School

Today Poinciana STEM Elementary School attracts K-5 students across Palm Beach County for its robust science, technology, engineering, and mathematics curriculum. The 572 Poinciana Panthers are a diverse student body, approximately half of its students are black, 22% white, 13% Hispanic, 8% Asian or Pacific Islander, and at 6 % or more identifying as 2 or more races.

Sources

- The Boynton Beach City Library Local History Archives

- The Boynton Beach News

- The Boynton Beach Star

- The Broward County Library Digital Archives

- Fisk University Special Collections & Archives

- The Florida Department of Public Instruction

- The Ft. Lauderdale News

- The Historical Society of Palm Beach County

- The Lake Worth Herald

- The New York Public Library Photographic Collection

- The Palm Beach County Property Appraiser

- The Palm Beach Post

- The School District of Palm Beach County

- Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library

- The State Archives of Florida

- The Sun-Sentinel

- The University of Florida

Special thanks to Georgen Charnes and Ginger Pedersen for their contributions to this research.

If you have any photos, comments, additions, or clarifications regarding Poinciana School and its history, please email boyntonhistory@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.