THE COQUIMBO SHIPWRECK: A TALE OF ADVENTURE, RESCUE, AND LEGACY

by Janet DeVries Naughton

The Coquimbo loaded with lumber, ashore 1/2 mile below the Boynton Hotel (Photo credit: Martin County Digital)

THE SHIP

In the early morning hours of a brisk January morning in 1909, the residents of Boynton awoke to a surprising sight. Just beyond the breakers, a large sailing ship loomed in the shadows, its masts towering above the water. The ship, a Norwegian barkentine named Coquimbo, had run aground on the offshore reef.

Built in Glasgow in 1876, the Coquimbo was a classic example of a lumber ship, designed to carry vast quantities of timber across the oceans. With two square-rigged masts forward and a schooner-rigged mast aft, the Coquimbo was a formidable vessel, one that had seen its share of rough seas and long voyages.

A small boat and several men readying to go out to the stranded Coquimbo (Photo credit: Martin County Digital)

The Coquimbo, destined for Buenos Aires, carried longleaf pine lumber grown in Gulfport, Mississippi. But as she sailed down the coast of Florida, disaster struck. Whether due to navigational error or the treacherous nature of the reef, the ship found herself hopelessly stranded. Aboard were fifteen men: three Swedes, one Dane, one Finn, and ten Norwegians, led by their captain, I. Clausen. They were now at the mercy of the sea and the elements, their ship a helpless giant stuck fast on the coral.

THE RESCUE

Word of the stranded ship spread quickly among Boynton residents. By midmorning, settlers rushed to the scene, eager to assist in the rescue. They crossed the canal, now known as the Intracoastal Waterway, on a hand-pulled skiff, determined to help the crew. According to oral history accounts, a breeches buoy transported the fifteen men to the beach.

For the next two months, the crew of the Coquimbo made their home on the beach, camping under makeshift tents fashioned from the ship’s sails. The weather was often chilly, and blustery, but the men endured, waiting for a steam tug to arrive from Key West to free their ship. The tug finally arrived, but despite days of effort, the Coquimbo remained stubbornly grounded. By May, the relentless pounding of the waves began to break up her hull, sealing her fate as a permanent fixture on the reef.

THE LUMBER

With the ship beyond saving, attention turned to her cargo: the precious lumber. According to pioneer Bertha Williams Chadwell, within days, a bonanza of long-leaf pine began washing ashore, scattered along a one-mile stretch of Boynton Beach. The settlers wasted no time in salvaging the timber. Families scrambled to pull the logs from the surf, stacking them in huge piles.

Men standing on the beach with dories laden with goods from the Coquimbo (shown in background) Photo courtesy of the Boynton Beach Historical Society

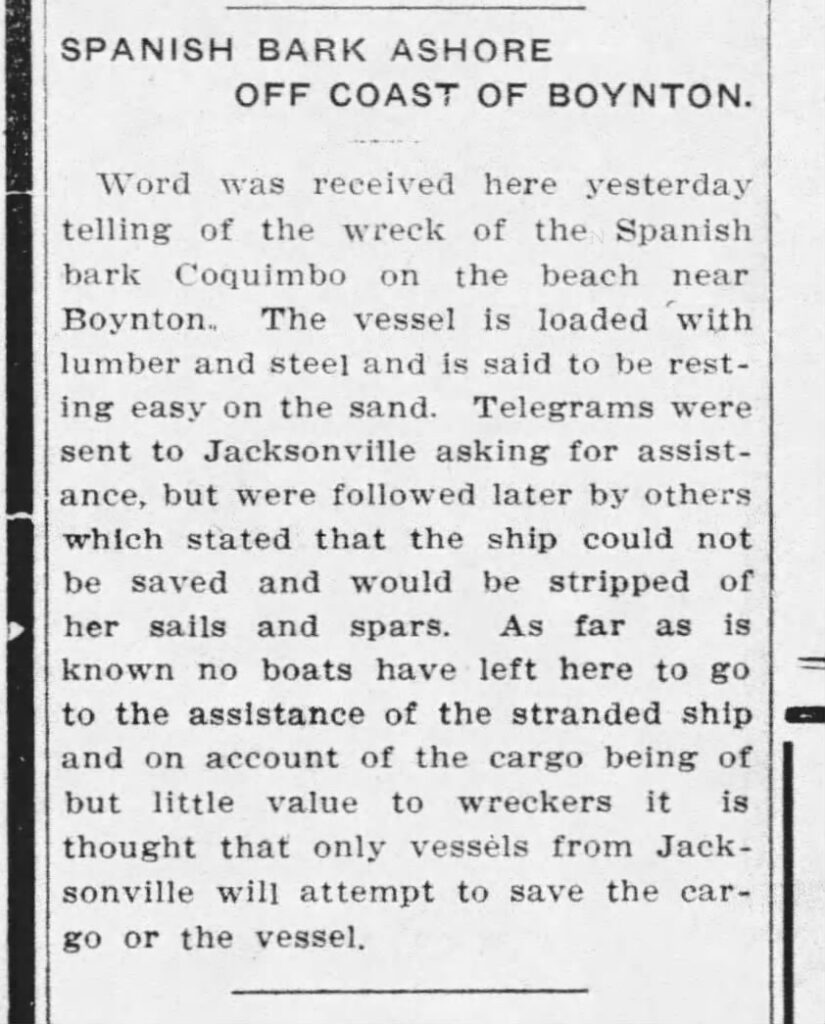

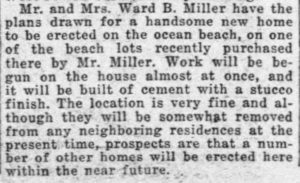

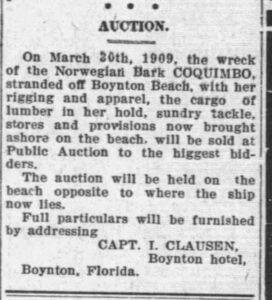

Capt. Clausen stayed at the Boynton Hotel and places ads in newspapers advising that the Coquimbo rigging, tackle, lumber and provisions were to be sold at Public Auction (24 Mar 1909)

A U.S. Marshall eventually arrived and declared that all the wood would have to be auctioned. However, he permitted the Boynton men to mark their piles, allowing them to purchase the lumber at low bids.

The remaining lumber was bought by a salvager from Key West, who had been informed of the wreck by the unsuccessful tugboat captain. This salvager constructed a miniature railroad that ran from the beach to the Intracoastal Waterway, using six oxen to pull a small car loaded with timber to a waiting barge. The lumber was then transported to Key West, where it was used to construct homes in what was, at the time, the wealthiest city in Florida.

THE LEGACY

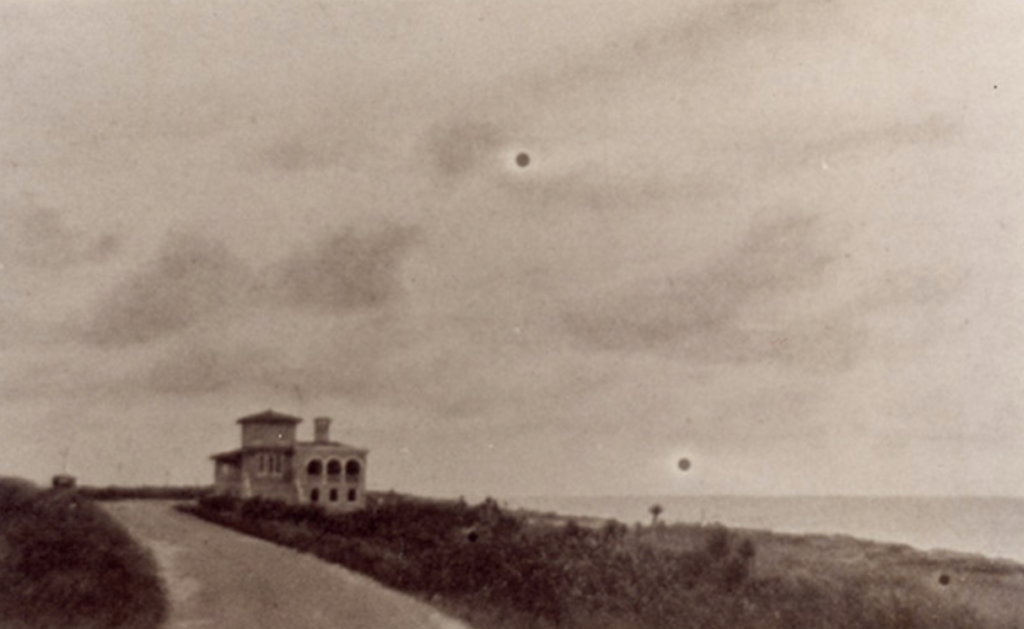

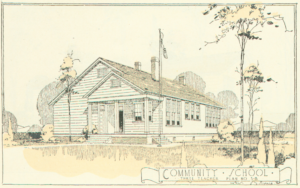

The Coquimbo’s lumber played a significant role in the development of Boynton Beach and the surrounding area. Many of the early homes and businesses in Boynton were built with the salvaged wood, including the original Boynton Beach Woman’s Club, which once stood on Ocean Avenue.

The Boynton Woman’s Club building on Ocean Avenue was built from lumber salvaged from the Coquimbo. The building lasted nearly a century and was demolished for the 500 Ocean apartment complex (Photograph: Richard Katz)

The ship’s salvaged bell continued to ring at First United Methodist Church for a couple decades, and today hangs outside St. Cuthbert’s Episcopal Church. The wood, auctioned to the settlers, became an integral part of the town’s architectural history.

SKELETAL REMAINS

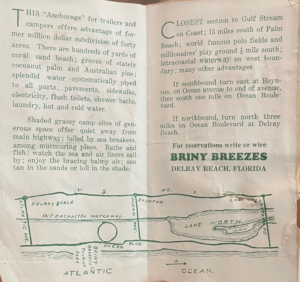

The Coquimbo herself, though, did not disappear entirely. In 1997, a magnetometer survey off the coast of Briny Breezes revealed remnants of a sailing ship. The survey team, led by local historian Steve Singer, concluded that the wreckage belonged to the Coquimbo. The ship’s bow, two masts, and other wreckage were now exposed, lying about 350 yards offshore in 15 to 17 feet of water.

An underwater photo of what Steven Dennison says is the 1909 wreck of the Coquimbo (2013, Steven Dennison photographer)

The wreckage was soon reburied under the shifting sands, only to be uncovered again in 2013 by Hurricane Sandy. It was during this time that Steven Dennison, a local resident, stumbled upon the shipwreck while snorkeling. Dennison had been exploring the waters off Ocean Ridge when he noticed something unusual on the ocean floor. As he swam closer, he realized he had discovered the long-lost Coquimbo. He found that the ship’s structure was remarkably well-preserved, with the bow, masts, and steering mechanism still intact. He shared his discovery with Joe Masterson, founder of the Marine Archaeological Research and Conservation group, who confirmed that the wreck was indeed the Coquimbo. By April 2013, the shifting sands had once again buried the ship, leaving no trace of her on the ocean floor.

LOCAL HERITAGE

The story of the Coquimbo is more than just a tale of a shipwreck; it is a story of resilience, community, and the enduring legacy of the past. The ship’s lumber helped build a town, and her wreckage continues to intrigue and inspire those who learn of her fate. The Coquimbo may be hidden beneath the sand, but her story lives on in the memories of those who cherish the history of Boynton Beach.

SOURCES

Blackerby, Cheryl. 2013. History Revealed: Sandy Uncovers Final Resting Spot of Norwegian Freighter The Coquimbo. The Coastal Star https://thecoastalstar.com/profiles/blogs/history-revealed-sandy-uncovers-final-resting-spot-of-norwegian-f

Castello, David. Wreck of the Coquimbo. https://www.boyntonbeach.com/history-of-boynton-beach/coquimbo/

Naughton, Janet DeVries. 2015. Discovery of Unusual Postcard of the 1909 Shipwreck Coquimbo and the Tale of Two Clydes. Boynton Beach Historical Society

Nichols, James H. 1980. The Wreck of the Coquimbo, Palm Beach Daily News

Singer, Steve. Norwegian Bark Coquimbo. https://www.anchorexplorations.com/bark-coquimbo-shipwreck?fbclid=IwY2xjawEyEA1leHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHVV-FT-WwwaH1fJmkGniYXtICj7sd6NnxfKUu6rnm-DNRrBCvIawlP8AHQ_aem_-qb8i1c6iBzglJoER1HWQQ

Willoughby, Hugh de Laussat II, 1885-1956, “Launching a boat, Winter 1912,” Martin Digital History, accessed August 20, 2024, http://www.martindigitalhistory.org/items/show/5992.

ORAL HISTORIES

Chadwell, Bertha Daugharty Williams, 1979, Boynton Beach City Library

Murray, Glenn L. 1978, Boynton Beach City Library

NEWSPAPERS

Daily Press, Newport News, VA

The Evening Mail, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Gulfport Record, Gulfport. Mississipi

The Macon Telegraph, Macon, Georgia

Miami Morning News-Record, Miami

The Miami News, Miami

The Ocala Evening Star, Ocala

The Palm Beach Post, West Palm Beach

South Florida Sun Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale

The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia

The Roanoke Times, Roanoke Virginia

South Florida Sun Sentinel, Fort Lauderdale

Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk, Virginia